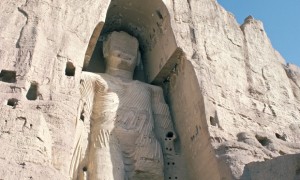

The Sasal Buddha at Bamiyan, Afghanistan, pictured before its destruction in 2001. Photograph: Ian Griffiths/Corbis

Lest we forget….

It is always a shock reaching Bamiyan, coming face to face with the two huge cavities in the cliff face. The upright tombs stare out over the valley, a splash of vegetation surrounded by wild mountains. The town straddles the Silk Road, close to the point where it used to enter Persia, dwarfed by two massive mountain ranges, the Koh-i-Baba and Hindu Kush. The void left by the two destroyed Buddha figures is appalling, it rouses an emotion almost more powerful than their once tranquil presence did for centuries.

To understand what happened you must go back to the beginning of 2001. The Taliban-led regime was on very poor terms with the international community and increasingly tempted by radical gestures. The decision to destroy the two monumental Buddha figures at Bamiyan was just part of the drive to destroy all the country’s pre-Islamic “icons”, an act of defiance to the outside world.

Demolition work at Bamiyan started at the beginning of March 2001 and lasted several weeks, the two figures – 58 and 38 metres tall – proved remarkably solid. Anti-aircraft guns had little effect, so the engineers placed anti-tank mines between their feet, then bored holes into their heads and packed them with dynamite. The world watched this symbolic violence in impotent horror.

Now almost 14 years on, reconstruction work has yet to start as archaeologists and Unesco policy-makers argue.

The two cavities resemble open wounds, a blemish on the long history ofAfghanistan, which experienced the fervour of Buddhism long before the arrival of Islam. For 15 centuries the two mystic colossi gazed down as the trading caravans and warring armies streamed past. Monks came from China to worship here. Others meditated in nearby caves.

The two Buddhas, draped in stucco robes, are testimony to a unique case of cross-breeding, which flourished in the early years of the first century AD, drawing on Buddhist influences from India and Greek aesthetics left behind by Alexander the Great. It gave rise to the kingdom of Gandhara and made a mark so deep that even the disciples of Allah, who reached here in the ninth century, made no attempt to disturb it.

Today the site has recovered a certain serenity. Children play volleyball below the cliffs and archaeologists work unhindered. Whereas a low-intensity war is still rumbling on elsewhere in Afghanistan, the central Hazarajat region and its capital Bamiyan (population circa 60,000) has been relatively spared. Most of the inhabitants are Shia Muslims and they had little sympathy with the Sunni Taliban from the Pashtun south. In the 1990s there was fierce fighting between the two sides. In Bamiyan there is a fairly enlightened view of Islam, and few women wear burqas. They proudly explain that 40% of girls in the province are in education, the highest proportion in Afghanistan.

So the outrage perpetrated by the Taliban came as a huge shock, a blow against a tolerant community that sees itself as unusual in the country as a whole. “The statues symbolised Bamiyan,” says mullah Sayed Ahmed-Hussein Hanif. Bamiyan had adopted and integrated the statues, making them a part of local legend. They had become an allegory for unhappy love, a foreshadow of Romeo and Juliet set in the Hindu Kush. He was Salsal, prince of Bamiyan; she was Shamana, a princess from another kingdom. Their love affair was impossible so, rather than live apart, they turned into stone, beside each other for all eternity.

“Local people had completely forgotten they were figures of the Buddha,” says Hamid Jalya, head of historical monuments in Bamiyan province. The Taliban and their dynamite reminded them of the original story. Ever since, people here have been unsure what to do about them.

Bamiyan residents in favour of rebuilding the Buddhas seem less concerned about Unesco’s insistence on using original materials. Photograph: Corbis

An incident in 2013 demonstrated the sensitivity of the subject. A decade ago Unesco authorised archaeologists and engineers to consolidate the two niches, with props and grouting. But nothing else. Almost two years ago someone noticed that, on the site of the small Buddha, a team from the German branch of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (Icomos) was beginning to rebuild the feet. This was contrary to Unesco policy, based on the 1964 Venice charter for the conservation and restoration of monuments and sites, which requires the use of “original material”. If work on the Bamiyan remains disregarded this rule, then the site would be struck off the World Heritage list. The Afghan authorities ordered the Icomos team to down tools, leaving the remains even less sightly than they were before.

The incident highlights the lack of a clear consensus on the future of Bamiyan both internally and among the international community. “Bamiyan seems emblematic of the way international aid has treated Afghanistan,” says Philippe Marquis, former head of the French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan (Dafa). There has been endless dithering, underhand rivalry, pointless discord and mistakes.

The Buddhas are a powerful symbol – of confessional tolerance, Buddhism in a Muslim country and the remains of the Silk Road – with scope for considerable political kudos, so academic quarrels have been diverted to serve strategic aims. The Afghans have watched this spectacle with growing amazement: Germany and its experience of post-war reconstruction; France and its archaeological exploits in Afghanistan; Japan and Korea, with their interest in the origins of Buddhism; Unesco and its byzantine bureaucracy. The various parties have sometimes cooperated with one another, but more frequently waged secret wars. “All these endless discussions among experts are pitiful, yielding no positive results,” says Zamaryalai Tarzi, a Franco-Afghan archaeologist who has been in charge of the French dig at the foot of the Bamiyan cliff for many years.

Behind the squabbling there is, however, a very real controversy as to how best to honour the fallen Buddhas. How should we go about making sense of an obscurantist crime the better to vanquish it? Or, in other terms, how should we mourn the martyrs? There are two opposing schools of thought: complete reconstruction or keeping the status quo. For now, the latter camp have the upper hand. “The two niches should be left empty, like two pages in Afghan history, so that subsequent generations can see how ignorance once prevailed in our country,” Tarzi asserts. Many other sites have adopted this approach, in particular the Genbaku dome in Hiroshima and the former summer palace in Beijing.

There is also a practical side: any attempt at reconstruction would be extremely complex. The original material, as required by the Venice charter, would be a major obstacle. The 2001 demolition left a heap of scattered fragments. Barely a third of the smaller Buddha has been saved, consisting of a pile of rock behind a wire fence. Furthermore, some of what does remain is from more recent additions. Over the centuries, long before the coming of the Taliban, the two figures were damaged and defaced. In the 1970s Indian archaeologists rebuilt the feet of the smaller Buddha using new material. Given this, how can the Venice charter rules be applied?

The final objection is that it may be a mistake to focus so much attention on the two Buddhas, given that the Bamiyan valley boasts many other exceptional sites, as yet little known. The ruins of the Shahr-e-Gholghola fortress, and probably monastery, perched on a hillock across the valley from the Buddhas, and the fortified town of Shahr-i-Zohak are both at risk, worn down by weather and earthquakes. “The priority is to save all the endangered sites around Bamiyan,” says Amir Fouladi, of the Aga Khan Trust. “There is no urgency about rebuilding the Buddhas.” The economic development of Bamiyan, due to gather speed with the projected launch of the Hajigak iron ore mines, makes it all the more important to adopt an overall strategy.

Meanwhile, the advocates of reconstruction have not wasted their time. Although the current mood is hardly in their favour, the small structure resting on the remains of the small Buddha’s feet suggests that the German branch ofIcomos has not given up hope. Its president, Michael Petzet, a professor at the Technical University of Munich, has made many statements in favour of at least rebuilding the smaller of the two figures. The local representative of Icomos Germany, Bert Praxenthaler, sees the controversy about the small Buddha’s feet as salutary in that it “stirred debate about what should be done with the Buddhas”. “We must be ready the day a decision is taken,” he adds. He is referring to the possibility that an ad hoc Unesco group may give the go-ahead for “partial re-assembly of the fragments”. His organisation sees this as an opportunity to demonstrate the quality of its restoration work in combining old and new materials.

Local residents are in favour. The idea of leaving the larger niche empty but rebuilding the smaller Buddha appeals to them, particularly as they take little interest in quarrels about original material. They are more concerned about boosting tourism in a relatively isolated area in desperate need of revenue. But there is symbolic value too. “By rebuilding a Buddha we could regain possession of our history and send a message to the whole world in favour of reconciliation between religions,” says Shukrya Neda, who campaigns for a local NGO. “By leaving the other niche empty we leave a testimony to the damage done by the Taliban.” Kabul has officially approved this approach, but some in Bamiyan feel its support is rather timid, for ethnic reasons. The Hazara population of Bamiyan distrust the Pashtun leaders in Kabul. “The government doesn’t want Bamiyan to develop its identity and economy,” says Riza Ibrahim, head of the city’s tourist board. “It’s discrimination.”

Unesco has tried to steer a cautious middle course on the issue of reconstruction. Its ad hoc expert committee has warned against rushing to make a decision. “It is neither for nor against reconstruction,” says Masanori Nagaoka, head of Unesco’s culture unit in Kabul. The committee has ruled that before considering partial reassembly of the small Buddha, a thorough technical and scientific study would be required. All of which favours keeping the status quo. Will the reconstruction lobby finally succeed in resurrecting Shamana (the small Buddha)? Perhaps, by dint of patience, but everyone seems to have overlooked an essential detail: the legendary prince and princess wanted to stay together forever. If Shamana rises again, but without Salsal, it would break their oath.

This article appeared in Guardian Weekly, which incorporates material from Le Monde

Following that one link and seeing what that German group was attempting to do with the Reconstruction on the feet of the smaller Buddha, I’d say it would be better to just leave it alone–their attempt look’s like crap–look’s like a stairway leading to a Bingo Hall or something.