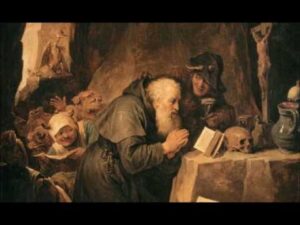

External forces, especially those arising from demonic sources, pose significant challenges for individuals on the Ascetic journey. These relentless assaults are among the most formidable barriers to be overcome. The Latin translation of “to besiege” was occasionally expressed as obsidere. This linguistic origin can be traced back to the English term “obsession.” Monastic records indicate that during this state, thoughts influenced by demons enclose the mind from external sources. By persistently troubling the mind with these thoughts, the demons attempt to hinder any contemplation of the Godhead. Accounts of this condition are plentiful in early monastic literature, ranging from the Life of St Antony, in which Antony laments that “the demons surrounded me like armed soldiers,” to the ascetical writings of Maximus Confessor in the seventh century, where he instructs that demons “encircle the mind with thoughts.” Or as the Psalmist best recounts it, “They encompassed me about; the encompassed me about like bees.” In accordance with the information shared in our prior blog post, the specific demon known as acedia afflicts and surrounds the mind.

As in the case of military sieges, the severity and length of demonic sieges could vary considerably. In extreme cases, this state could last for several years or even decades. To give but a few examples, Cassian reports of a monk who was incessantly besieged (jugiter obsedisset) by a thought of fornication for fifteen years. Elsewhere we read of a monk who was constantly tempted by horrible thoughts for nine years, as well as of another who fought for twelve years against a thought that did not leave him alone even for a moment; and John Climacus, as noted earlier, speaks of a monk who was continuously harassed by a blasphemous thought for two whole decades. While the precise number of years reported in monastic sources may not be accurate, there is little doubt that demonic sieges were often a prolonged and agonizing experience.

Yet Cassian clearly distinguishes between this form of assault, in which a demon assails a person from outside by means of thoughts, and more severe cases of demonic possession in which a demon takes up residence inside the person. The more control the demon gains over the individual, the more the latter falls into bondage and loses his own identity. (Graiver, Asceticism of the Mind, pg. 138)

Obsessions are repetitive and intrusive thoughts, images, or impulses that are not wanted or accepted and lead to personal resistance. Some obsessions may arise simply from the excessive effort to control one’s thoughts: a regular unwanted thought can turn into an obsession when attempting to suppress it under conditions of increased mental strain, such as fatigue or anxiety. Trying to suppress it further becomes increasingly challenging as the individual becomes highly anxious about their mental state. The only distinction between regular unwanted thoughts and obsessions is that the latter are more intense, longer-lasting, and more frequent, cause greater discomfort, and are strongly resisted. Additionally, the content of an obsession generally remains consistent over time. as psychiatrist Jeffrey Schwartz puts it:

[Obsessions] seem to arise from a part of the mind that is not you, as if a hijacker were taking over your brain’s controls, or an impostor filling the rooms of your mind. The sufferer feels like a marionette at the end of a string, manipulated and jerked around by a cruel puppeteer. (ibid, pg. 143)

Severe mental fixation, in which fixation controls a person’s life, is regarded as a symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). My mother suffered from this condition throughout the majority of her life, which ultimately resulted in the development of full-blown Alzheimer’s Disease. From my earliest recollections, it was customary for us to wait in the vehicle while she remained indoors, compulsively verifying whether the oven had been turned off.

Religious OCD, commonly referred to as “religious scrupulosity,” is a distinct form of OCD characterized by an individual’s obsessive fixation on religious and moral anxieties. This condition is typified by scrupulosity, which is an excessive preoccupation with moral uprightness and an undue apprehension regarding the occurrence of blasphemous thoughts. Throughout my previous blog posts, I have repeatedly mentioned my experiences in the confessional with individuals who suffer from this particular ailment. Their persistent confessions regarding their morbid obsessions can be quite overwhelming and may even lead one to a state of madness. One of the numerous hazards that are intrinsic to religions.

Despite the somber tone of the aforementioned, it is important to note that spiritual aid remains accessible:

As noted earlier, Climacus tells of a “zealous monk” who was beset by a blasphemous thought for two whole decades. After twenty years of futile struggle, the monk decided to write the thought down on a sheet of paper, which he handed to a certain holy man. Climacus reports: The old man read it, smiled, lifted the brother and said to him: “My son, put your hand on my neck.” The brother did so. Then the great man said: “Very well, brother. Now let this sin be on my neck for as many years as it has been or will be active within you. But from now on, ignore it.” And the monk who had been tempted in this fashion assured me that even before he had left the cell of this old man, his affliction (τὸ πάθος) was gone.

In his role as a burden bearer, the spiritual father was able to induce an immediate and lasting cure by taking upon himself the moral responsibility for his disciple’s hideous thought. As one of the desert fathers describes the therapeutic effect of this procedure, “He who has a spiritual father casts all his concern upon him and is without care in all things and no longer in fear of judgement by God.” (ibid, pg. 148)

The phenomenon observed in this potent therapeutic approach of trust and faith is the relinquishment of the disciple’s deeply ingrained sense of responsibility for their own thoughts, which is transferred to the spiritual father and ultimately back to the Godhead Itself. It is widely acknowledged within the Buddhist philosophy that the mind possesses the ability to self-heal. However, it is imperative for individuals to harness their capacity for attention, which is a recurring theme in both traditions. The cultivation of this capacity requires a sustained effort to retrain attentional habits. As such, attention can serve as a point of convergence between these traditions, enabling us to examine the practical aspects of all forms of asceticism.

What are the self-help measures that can be employed to overcome these mental demons, whether personal or otherwise? The practice of detached self-observation instructed ascetics to create a distance between themselves and afflictive or undesirable thoughts. Through this process, thoughts were stripped of their personal significance and importance, resulting in the dismantling and discarding of obsessions. The repeated acts of self-disclosure and detached introspection not only facilitated the healing of dysfunctional thinking patterns but also had a profound impact overall. Making an “examination of conscience” is the most utilized modality in combating obsessions. These were all carried out in the context of a relation of complete obedience to a spiritual father. On these occasions ascetics were expected to disclose all their thoughts to the spiritual father in order that they might be thoroughly examined and then later discarded. The practice of conducting an “examination of conscience” is widely employed as a means of combating obsessions. Such examinations are typically conducted within the framework of a relationship characterized by complete obedience to a spiritual mentor. During these sessions, ascetics are expected to divulge all of their thoughts to their spiritual mentor, so that they may be thoroughly scrutinized and subsequently relinquished. During our time in seminary, we were taught to utilize this methodology that has its roots in the spiritual exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola.

According to the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, this form of detached introspection enabled the monk to distance himself quickly from the thought at the time of temptation. As thoughts are witnessed and discerned, they are simply “let go.” The ascetic who cultivated this skill thereby learned to distance himself from the affective power of his mental content. The less the mind was identified with the content of its thoughts, the greater became its ability to concentrate, and the greater the resulting sense of calm. With repeated practice, thoughts no longer stimulated the emotions or distracted the practitioner. Such mental concentration, described in monastic writings as a state of dispassion or purity of heart, could be maintained even while the monk carried out his usual activities; it became a habitual awareness in his day-to-day life of God’s presence in whatever he may be doing at that moment. The state of dispassion thus marked a decisive turning point in the spiritual itinerary of the monk. It could lead to more exalted mystical experiences in which the mind transcends all thoughts and multiplicity. (ibid, pg. 176)

The Buddha, too, employed this methodology of a spirit of dispassion:

“And what is the noble method that is rightly seen and understood by discernment? From the arising of this comes the arising of that. When this isn’t, that isn’t. From the cessation of this comes the cessation of that. “This is the noble method that is rightly seen and rightly ferreted out by discernment.” (Anguttara Nikaya 10.92)

In both spiritual traditions, the state of apatheia, characterized by the absence or suppression of passion, emotion, or excitement, is recognized. It denotes a lack of interest or concern for things that others may find moving or exciting, commonly referred to as disinterest. However, it is important to note that apatheia is not considered the ultimate objective of the spiritual journey, but rather serves as the fundamental basis for contemplation, which enables the mind to Recollect and restore its true and unbridled nature. Undoubtedly, it is through this manner that obsessive and compulsive thoughts are best conquered, whether they are of demonic nature or otherwise.