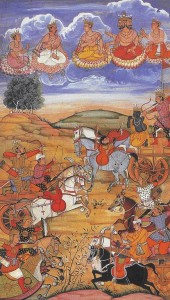

Our epic opens on the Kurukshetra (field of Kuru) Battlefield; arrayed are the vast armies of the opposing families, the Pāndavas and Kurus. This action taking place is the supreme dharma-kshetre, (on the field of dharma). Hence we are on an immense Dharma-field—the place where the Sacred Yoga of the Spirit is about to commence. Dhritarāshtra, is the blind ruler of the Kurus. Allegorically, he is blind due to his own avidya (inner-ignorance) of the True Dharma and therefore his armies are the destroyers (adharma) of Truth. He calls out to Sanjaya, his trusted minister and visionary.

1.1 O Sanjaya, on the dharma-field of battle at Kuru, my personal army and the armies of Pāndu’s sons has already gathered. How did it all turn out?

Notice how Dhritarāshtra utilizes the past tense—how DID it turn out? The armies have just been arrayed, the action apparently hasn’t even begun, and yet he’s already inquiring of the battle’s outcome. This is a literary technique designed to convey that this Cosmic-Dharma-Battle has been occurring time and time again throughout the millennium; its contestants are legion.

Sanjaya responds,

1.2 Yes, your son Duryodhana, the king, has prepared his forces for battle with the armies of Pādava; he is now approaching his teacher, Drona and inquires…

Sanjaya occupies a central position in the Bhagavad Gita. He is personal-minister to Dhritarāshtra but at the same time a mystic seer. He is the consummate teacher, or yogin-guru; he has the yogic siddhis to see into the minds of Arjuna and Krishna in their upcoming dialog. as well as what is to transpire on the battlefield. In this sense, he is the true Yogin Extraordinaire. Graham H. Schweig writes:

The words of Sanjaya fall into three categories: dialogical, narrative, and rapturous. The text begins with the dialogical, when the king, Dhritarshtra, asks Sanjaya in the first verse what is occurring on the battlefield. Sanjaya responds to the king using narrative discourse, as he relates the events at Kurukshetra. In the next nine verses he quotes the king’s eldest son, who, from the battlefield, reports on the might of the two armies. Throughout the Gt, while narrating events, Sanjaya occasionally addresses the king in dialogue. His narrative words are his dominant form of expression, however, as he transmits either what is taking place on the battlefield or the interactions between Arjuna and his charioteer. Through his special extrasensory power, Sanjaya functions as the visionary minister for the king and the transmitting teacher for the reader of the Gt. Not until the final verses of the text do we encounter Sanjaya’s third type of expression, that of rapturous words, in a suite of verses that begins with the following:

Thus from Vsudeva and Prtha, whose self is exalted, I have heard this wondrous conversation, which causes a state of rapturous bliss. (BG 18.74)

These rapturous expressions, along with those of dialogue and narration, demonstrate Sanjaya’s powerful presence as a blissful and compassionate deliverer of souls. Sanjaya thus functions as the archetypal guru, a prominent role in India from ancient times. Schweig, Graham M. (2010-09-28). [Bhagavad Gita: The Beloved Lord’s Secret Love Song (Kindle Locations 6020-6038). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.]

So, Sanjaya is a Virgil-like character who will lead us through the mysteries of the dharma-field yet to come.

Drona: interesting how he was once master of both opposing leaders in the art of archery, but now he has sided with the Kurus.

1.3 “My noble teacher, behold this great Pandava Army—arrayed by your own favored student who is bent on revenge.”

1.4 Also assembled are Heroes, Mighty Archers, Magnificent Warriors who are the equal of Arjuna and Bhima, as well as Yyudhana, Virata, and even Drupada—your sworn rival, seated on his own glorious chariot.

Bhima: brother of Arjuna, whose name means the tremendous one, born as he was from the loins of Kunti by the Wind God, Vāyu.

Yyudhana: a Pandava ally—his name meaning, “anxious to fight.”

Virata: another Pandava ally, a warrior king from whom they once took refuge.

Drupada: chief of the Pandava army—his name means “quick-step”.

Other highly honored warriors from both sides of the field continue to be heralded just before the great “cry to battle” is sounded from the Conch Shells. The Kurus blow their Conchs first, and then the Glorious Sound of the Divine Conch Shells emanating from the direction of Arjuna and Krishna’s Noble Chariot, fills the air and strikes fear in their opponent’s rattling bones. Paramahansa Yogananada indicates that this passage’s awe-inspiring Noble Sound is likened to that of the Sacred OṀ, vibrating through the inner-channels of the Chakras within the Yogin’s body. This indicates the Yogin’s success in withdrawing one’s consciousness from the samsaric realm and rendering all outside disturbances silent, while simultaneously ascending to the higher ceilings of Noble Self-Realization through the Chakras.

It’s interesting to note that for a Lankavatarian, too, the symbol of the Conch Shell strikes a high mystical chord. I’m reminded of the figure of Naga Kanya, extending the Primordial Mystical Conch Shell with her hands as if beckoning the Yogin to spiritually benefit from the hidden blessed bodhi-pearl within.

Sanjaya’s gnosis occurs via what could be called “mind-to-mind transmission” in Buddhism and arises from the mystical recognition of the spirit of Krishna homologous to the Buddha principle.

Fascinating…

It might be worthwhile observing too that Sanjaya’s gnosis of the transcendental meeting of Arjuna and Krishna transmits through Vyasa. It is clear Sanjaya, Vyasa, Arjuna, and Krishna all are of the same spirit (“Buddha nature”), but because Sanjaya does not directly behold Krishna (except via transmission) his gnosis is at a different level of recognition than Arjuna, who beholds Krishna face to face so to speak in the form of the charioteer. Further, Sanjaya describes this encounter as “hair raising”, and this poetic reminder of the skandhas should not be overlooked; the yogin has experienced something so beyond the ordinary mind’s normal frame of reference, that it has thrilled him to the bones. This reference to the psychophysical, which is not a condition that limits Krishna, demonstrates the profound effects of gnosis on the world of form, and further demonstrates the flexibility of subtle consciousness which transcends all form.

Varjagoni’s comparison to Virgil in Dante’s Divine Trilogy is a very apt simile, because even though Sanjaya’s attainment of siddhis has enabled him to recognize Krishna, he is still far from a “fully” knowing guide who can behold Krishna directly. This humanizes the poetic character of the verse and is a compassionate reminder to the hearer that even though Krishna affirms disinterest of the Supreme Spirit in the affairs of men throughout, the presentation of Sanjaya as distant from Krishna and yet inseparable, allows us to see that all human beings, who are obscured, have the spirit of Krishna and are inseparable from this emanation of the absolute (i.e. have Buddha nature.)