This series would be incomplete if I did not share some personal psychedelic anecdotes from my own past. In my late teens and early twenties I used to smoke marijuana in social settings with my friends. These occasions were always filled with fun and laughter. There was one instance while getting high at dusk in a wooded area that I envisioned a GIANT pair of disembodied Keds Sneakers (the old kind with the high backs) walking down the path in our direction as everyone howled with laughter. Another time I was driving past my first family home that we used to live in (direction heading west) and pointing out to my passengers “here, we used to live on that side of the road (pointing left).” Then, at the end of the street we turned-around and proceeded driving down the road again (direction heading east) as I pointed out, “here, we used to live on THAT side of the road (pointing right). You had to be high while appreciating this. But by far the most singular episode occurred while living in the wilds of South Florida in 1980. At that time I was working at assorted jobs to pay my way through college; one of them was at a place named “The Olde Fashioned Cookie Junction”, a locale inside one of the shopping Malls. While working with a girl named Dawn, we both were smoking some Sensimilla. Now Sensimilla is a most highly concentrated form of cannabis that, unlike other forms, contained no seeds. Here’s a more full representation:

Sensimilla refers to many strains of marijuana where the female plant is allowed to only produce flowers, but is left unfertilized so does not progress on to produce seeds.

Its unfertilized state contributes to the plant’s ability to produce higher levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and other cannabinoids that are used to render the physical psychoactive response commonly known as a ‘high’ in individuals. Sensimilla is Spanish and translates into ‘without seeds’.

In other words, my friends, this is a most virgin form of pot—VERY potent and marvelously effective—it produces strange siddhis. Once, we were waiting on a woman at the counter and just glancing at this woman we somehow “knew” all about her, the sad, illusional pretense, ect; Dawn glanced over in my direction and said, “I know”. It was a most telepathic encounter between the two of us. Timothy Leary once described it this way:

It was straight telepathic communication. I was in his mind, he was in my mind, we both saw the whole thing, the illusion, the artifice, the flimsy game-nature of the mental universe. The popeyed look of terror changed to mellow resignation and the Buddha smiled.

After those early days I haven’t partaken in marijuana or any other psychedelic substance. The only thing I’ve tried recently is some Hemp-Oil purchased on Amazon, to help alleviate my arthritis. I’ve always wondered though, if I tried Sensimilla again today, would I have the same reaction? Perhaps a twenty-something brain was more susceptible, since it was still forming. Would it have the same effect on my 62 year-old noggin?

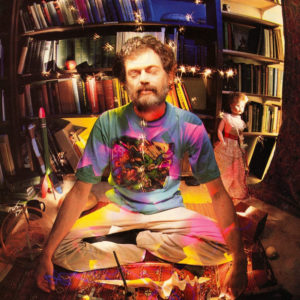

One of the best advocates for the use of psychedelic plants was Terence Kemp McKenna (1946-2000). As Wiki states:

Terence was an American ethnobotanist, mystic, psychonaut, lecturer, author, and an advocate for the responsible use of naturally occurring psychedelic plants. He spoke and wrote about a variety of subjects, including psychedelic drugs, plant-based entheogens, shamanism, metaphysics, alchemy, language, philosophy, culture, technology, environmentalism, and the theoretical origins of human consciousness. He was called the “Timothy Leary of the ’90s”, “one of the leading authorities on the ontological foundations of shamanism”, and the “intellectual voice of rave culture”.

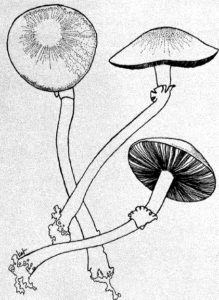

Let us focus now on one of his writings, Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge. His drug of choice, Psilocybin (or mind-expanding Mushrooms)

No stranger to indigenous cultures and their mystical utilization of hallucinogens, he writes:

Obviously, we cannot continue to think about drug use in the same old ways. As a global society, we must find a new guiding image for our culture, one that unifies the aspirations of humanity with the needs of the planet and the individual. Analysis of the existential incompleteness within us that drives us to form relationships of dependency and addiction with plants and drugs will show that at the dawn of history, we lost something precious, the absence of which has made us ill with narcissism. Only a recovery of the relationship that we evolved with nature through use of psychoactive plants before the fall into history can offer us hope of a humane and open-ended future.

Hinduism and Buddhism have maintained traditions of techniques of ecstasy that include, as stated in the Yogic Sutras of Patanjah, “light filled herbs,” and the rituals of these great religions give ample scope for the expression and appreciation of the feminine. Sadly, the Western tradition has suffered a long, sustained break with the sociosymbiotic relationship to the feminine and the mysteries’of organic life that can be realized through shamanic use of hallucinogenic plants. (ibid)

My main appreciation of McKenna is his own unique link with Shamanism:

The mystery of our own consciousness and powers of self-reflection is somehow linked to this channel of communication with the unseen mind that shamans insist is the spirit of the living world of nature. For shamans and shamanic cultures, exploration of this mystery has always been a credible alternative to living in a confining materialist culture.

Mircea Eliade, author of Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy and the foremost authority on shamanism in the context of comparative religion, has shown that in all times and places shamanism maintains a surprising internal coherency of practice and belief. Whether the shaman is an Arctic-dwelling Inuit or a Witoto of the Upper Amazon, certain techniques and expectations remain the same.

In short, the shaman is transformed from a profane into a sacred state of being. Not only has he effected his own cure through this mystical transmutation, he is now invested with the power of the sacred, and hence can cure others as well. It is of the first order of importance to remember this, that the shaman is more than merely a sick man, or a madman; he is a sick man who has healed himself, who is cured, and who must shamanize in order to remain cured.’

It should be noted that Eliade used the word “profane” deliberately with the intent of creating a clear split between the notion of the profane world of ordinary experience and the sacred world which is “Wholly Other.”

Many do not realize that shamanism also has a direct link with Buddhism, in particular, Vajrayana Buddhism. Samuel Geoffrey in his excellent book, Civilized Shamans, sets the record straight:

One of the most important contrasts between clerical and shamanic Buddhism is that Clerical Buddhism is scriptural, and it relates to the text as a source of rational argument. Shamanic or Tantric (Vajrayana) Buddhism is oral, and it derives from a lineage of teachings that can be viewed as having originated in a ‘primal time’ or ‘Great Time’ of myth.

My contention (which is not particularly original) is that certain aspects of Vajrayana (Tantric) Buddhism as practiced in Tibet may be described as shamanic, in that they are centered around communication with an alternative mode of reality (that of the Tantric deities) via the alternate states of consciousness of Tantric yoga.

Hence, I use the term ‘shamanic’ as a general term for a category of practices found in differing degrees in almost all human societies. This category of practices may be briefly described as the regulation and transformation of human life and human society through the use (or purported use) of alternate states of consciousness by means of which specialist practitioners are held to communicate with a mode of reality alternative to, and more fundamental than, the world of everyday experience. (Civilized Shamans)

There have been many series here at Unborn Mind Zen that reinforces this Shamanistic perspective. One in particular, Notes from the Iron Stupa, is concerned with Shamanistic Initiation: This is symbolic of the condition into which the ascetic’s body must fall if his spirit is to enter into sambhokayic reality. It bespeaks the severance from samsaric reality by dismembering the skandhic apparatus—highlighted by the ritual of “Chöd”, or cutting-off. Symbolically this signifies severance from all forms of attachment, whether physical, emotional, mental and above all, spiritual; hence this dismemberment-resurrection theme is a critical initiatory junction in which ordinary samsaric-reality is erased in favor of the Real Nature of the Dharmadhatu.

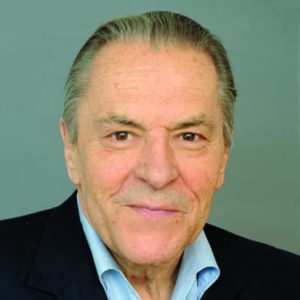

Another prominent personage to consider in this series is Stanislav Grof (1931–) a Czech psychiatrist, (perhaps best known for his pioneering work in Holotropic Breathwork—inclusion mine) one of the founders of the field of transpersonal psychology and a researcher into the use of non-ordinary states of consciousness for purposes of exploring, healing, and obtaining growth and insights into the human psyche. (Wiki)

Grof worked extensively with LSD therapy, in particular how it interacted with one’s psyche. His most famous work in this subject matter is LSD: Doorway to the Numinous. LSD in effect is a marked intensification of all mental processes and neural processes. For the most part, Grof’s observations with his patients have little in common with the experiences of Huxley and Leary, rather they indicate psychosomatic dysfunctions, especially those that were sexual in nature.

In the initial stages of psycholytic treatment, psychodynamic experiences can dominate many consecutive sessions before the underlying unconscious material is resolved and integrated and the patient can move to the next level…

Under the influence of LSD, such subjects experience regression to childhood and even early infancy, relive various psychosexual traumas and complex sensations related to infantile sexuality, and are confronted with conflicts involving activities in various libidinal zones. They have to face and work through some of the basic psychological problems described by psychoanalysis, such as the Oedipus and Electra complexes, castration anxiety, and penis envy.

In spite of this far-reaching correspondence and congruence, Freudian concepts cannot explain some of the phenomena related to psychodynamic LSD sessions. For a more complete understanding of these sessions and of the consequences they have for the clinical condition of the patient, as well as for the personality structure, a new principle has to be introduced into psychoanalytical thinking. LSD phenomena on this level can be comprehended, and at times predicted, if we think in terms of specific memory constellations, for which I use the name “COEX systems” (systems of condensed experience).This concept has emerged from the analyses of the phenomenology of serial LSD sessions in the early phase of my research in Prague. It proved unusually helpful for understanding the drug-induced psychodynamic experiences during the initial stages of psycholytic therapy with psychiatric patients.

Indeed, this COEX (systems of condensed experience) seem to be the end-all of everything for Grof. It can be defined as a specific constellation of memories consisting of condensed experiences (and related fantasies) from different life periods of the individual. For me, he is too clinical—although that is the nature of his profession. All too-often these clinical types appear to orchestrate their sessions in such a fashion that negative flashbacks become the primary factor in a person’s psychic makeup. He’s still somehow more like Freud than Jung in this matter. At least Jung emphasized the wider vistas of the Collective Unconscious forces that take on “mythic proportions”—a more all-inclusive pattern that encompasses the holistic-mind rather than the most dark and disturbing parts, or shadow-reality. Although to his credit he includes the use of Psilocybin in catalyzing spiritual experiences.

Here’s a staggering statistic for your consideration, found during my research:

Marijuana is usually forbidden, but alcohol and nicotine—far more destructive drugs—are consumed in mass quantities. While psychedelics are outlawed, 27 million Americans currently take antidepressants such as Zoloft or Prozac. These days, most people are far more suspicious of plant compounds safely ingested by human beings for tens of thousands of years than they are of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or other powerful, utterly synthetic, mood and mind-altering drugs created in the last decades by a pharmacological industry motivated by profit. Antidepressants fit society’s underlying Psychedelics.

[Also, let’s not forget today’s highly-destructive opioid epidemic!]

Well, I hope that you’ve found this series as fascinating and helpful as I have in its preparation. The title for this concluding blog of the series, A Colorful Island in Space, is in reference to a line delivered by Dr. Smith of Lost in Space fame.

He was my favorite character on the sci-fi show from the sixties and was always getting himself deeper and deeper into mischief of every sort throughout the three-year run of the series. This was balanced by the character of young Will Robinson and the family Robot, who together always tempered Dr. Smith’s antics with timely “Rationality”. Metaphorically we can see that William Robinson was the voice of conscience for Dr. Smith to amend his nefarious ways. He is the WILL-factor that was referenced in the previous blog of this series, one that must remain predominant over the wild and Colorful Islands in Space of psychedelia. While I perhaps wouldn’t mind one day revisiting Sensimilla, I need to walk-back somewhat from stating in the previous blog that I would be willing to try LSD. After reading Grof I am more hesitant on this point, I wouldn’t like to end-up like good ol’ Dr. Smith emoting “Oh, the pain, the pain!” Then again, if I’m accompanied by someone who is not a therapist-clinician (like Grof), perhaps I could better experience the thrill of the ride. Although, I must say in conclusion that I’ve always become more “spiritually-high” while writing these blog series, in particular, the exegesis on the Sutras, such as The Vajrasamādhi Sutra. Who could not become “high”, provided one is instilled with Right Mindfulness, with the following exchange from the Vajrasamādhi:

“How can one prompt those sentient beings not to give rise to a single thought?”

The Buddha replied: “One should prompt those sentient beings to sit with their minds and spirits calm, abiding in the adamantine stage. Once thoughts are tranquilized so that nothing is generated, the mind will be constant, calm, and serene. This is what is meant by the absence of even a single thought.” Muju Bodhisattva said: “This is inconceivable! When one is enlightened to the fact that thoughts are unproduced (emphasis mine), one’s mind becomes calm and serene. That is the inspiration of original enlightenment.”

Varjagoni