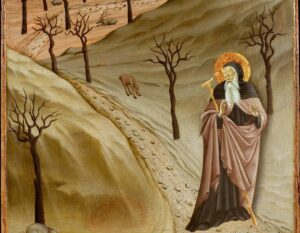

The most renowned of all western desert solitaries was St. Antony of Egypt (251-356 CE). He was a disciple of St. Paul of Thebes and began to live an ascetic lifestyle at the age of 20 and 15 years later left for complete isolation in a mountain near the Nile called Pispir (now Dayr al-Maymūn). During his retreat, he conducted a legendary battle with the Devil and defeated a series of temptations which are known by Christian theology and iconography. When 305 arrived, Antony departed his retreat to educate and lead a monastic life. After Christian persecution ended through the Edict of Milan (313), he went to a mountain between the Nile and Red Sea where the monastery Dayr Mārī Antonios still stands. He kept receiving visitors there; he also traversed across deserts to Pispir twice. The last time he visited Alexandria was c. 350 when he proclaimed against Arianism heresy which declared that Christ was not of equal essence as God the Father. (Britannica)

To reinforce, at the start of his life, Antony withdrew into a solitude that grew increasingly intense. He isolated himself in an old fort for two decades, refusing to communicate with anyone. Things changed drastically when he was fifty-five: his friends broke down the door and he emerged from the fortress. Though the next fifty years were spent living in the desert apart from two trips to Alexandria, spiritually he returned to society. He became available to others, taking on disciples and providing spiritual guidance to all who visited him. His biographer Palladius recounts this ministry of spiritual guidance through the story of Eulogius and the cripple: it provides a vivid example of how Antony exercised this role. Bracketing all of this was Antony’s austere physique:

Remarkably, the Life of Antony contains a description of what appears to be aging retardation/reversal effects associated with the ascetico-meditational regimen of the “Father” of Christian asceticism, and these effects are strikingly similar to tissue changes described in the New England Journal of Medicine study on growth hormone. “Contemporaries liked to think that they sensed [the “original, natural and uncorrupted” Adamic prefallen state] in Antony, when he first emerged from his cell at the bottom of a ruined fort, after twenty years, in 305 writes Brown, who goes on to quote the Life:

When they beheld him, they were amazed to see that his body had maintained its former condition, neither fat for lack of exercise nor emaciated from fasting and combat with demons, but just as it was when they had known him previous to his withdrawal.

Although Antony was not administering exogenous growth hormone to himself, the description suggests, in light of the evidence reviewed here and elsewhere, the compelling possibility that the changes—or absence of changes—observable in him resulted from the stimulation of enhanced endogenous growth hormone activity by ascetico-meditational practice. The Life goes on to relate that Antony lived beyond the age of one hundred and that his passing represented more of a direct entrance to Paradise than a typical death. Moreover, Athanasius’s description of his last years suggests other features consistent with aging retardation/reversal.

. . . in every way [Antony] remained free of injury. For he possessed eyes undimmed and sound, and he saw clearly. He lost none of his teeth—they simply had been worn to the gums because of the old man’s great age. He also retained health in his feet and hands, and generally he seemed brighter and of more energetic strength than those who make use of baths and a variety of foods and clothing…

And the description of Antony’s super-healthy condition is also consistent with the results of research on the antiaging properties of the hormone melatonin, the actions of which I have proposed are also enhanced through ascetico-meditational practices. (Vincent L. Wimbush & Richard Valantasis, Asceticism, 566-567)

While several practices of the ascetico-meditational regimen are likely to result in increased secretion of melatonin, the one with the most pronounced potential is likely to be immobilization in darkness. Recent research has shown that humans who are relatively immobile in extended periods of darkness experience increased levels of melatonin secretion. Other research has demonstrated the profound antiaging effects of melatonin in humans and animals. Several very recent studies in particular graphically demonstrate the potentially profound antiaging effects of melatonin. (ibid)

Ethiopian Christian hermits also displayed this melatonin impact, specifically esteemed individuals (such as saints), who are frequently mentioned in “angelic” descriptions; angels who possess both a youthful and androgynous nature. Likewise, in the Eastern context, the Chuang Tzu makes reference to an elderly hermit residing in the mountains, described as having skin resembling ice or snow, and being gentle and timid like a young girl.

Antony also focused on the notion of resurrection as the restoration of man’s original nature, rather than solely the final resurrection in the future. Unlike mentioning the resurrection of the body, Antony’s letters only discuss the resurrection of the mind. This resurrection is seen as a cognitive and pneumatic action that deems the body insignificant. Truly there are parallels within Buddhism in terms of the primacy of one’s Original Nature. His letters serve as the sound spiritual testament of a true master; yea, he was what could be called a charismatic teacher of spiritual gnosis. They were written to ensure that his disciples remain focused on comprehending spiritual matters correctly and persevering in their spiritual practice in sound and practical ascesis. At the same time, it also needs to be stressed that Antony did not identify as a Gnostic; rather, he followed the conventional teachings of the catechetical school of Alexandria.

Of concurrent interest, if the controversy surrounding Origen (c. 185 – c. 253) could be attributed to someone other than Origen himself, there is substantial evidence indicating that the ascetic monk Evagrius Ponticus (c. 345 – c. 399), his most prominent disciple, played a significant part. Evagrius agreed with Origen’s idea of Apokatastasis, which can be understood as the restoration and ultimate unification of all souls through faith, including the reconciliation of the devil and his followers. Essentially, this concept aligns with Buddhist beliefs that even the most intense realms of suffering are temporary and will eventually be purified and restored. In this particular study, the author emphasizes the importance of discarding all images, which aligns with our own Lankavatarian principles. While the exact answer regarding the comparison of God’s “light” and the light of the mind remains uncertain, it is evident that God’s “light” is formless, shapeless, and immaterial. This teaching further emphasizes Evagrius’s unwavering belief in the complete “imagelessness” of the mind during contemplative prayer. Any image that exists in our minds is considered idolatrous, akin to a god. Thus, according to Evagrius and his Origenist colleagues, the concept of the “image of God” is no longer attainable to the nature of our fallen and ignorant state. However, what is unfortunately accessible to us, and in great abundance, are “images” that emerge from visual impressions, memories, dreams, fantasies, and even demonic influence. By examining Evagrius’s theory on how these images impact the human mind, we ultimately uncover the core of Evagrius’s ascetic and anti-iconic theology: the mind itself, characterized as a receptive entity for images, becomes the ultimate battleground in the fight against “images.”

Antony’s letters did predominantly emphasize gnosis (knowledge), which is their most noticeable aspect. The letters consistently urge individuals to seek and comprehend knowledge, which stems from a theology that places knowledge at its core. Knowledge is vital for salvation, as it enables one to reconnect with the Godhead. This gnosis primarily pertains to self-awareness: understanding oneself is a prerequisite for understanding the Absolute, and rediscovering oneself is necessary to reunite with Source Itself. To be freed from the constraints of the material and transient, the physical body must be purified and subjugated to the spirit.

Asceticism in Antony’s letters is a necessary first step in the human being’s return to God. The human being is torn apart by passions attacking through the senses and ideas attacking through the mind. He or she has no power over self, but has become a seat of unclean motions and demons. The latter must be driven out and the body and the soul cleansed. Ascetic practice is the method of cutting short the influences of the motions and demons.

What Antony realized was that it is impossible to live a fully ascetic life—that is, a life marked by spiritual warfare—within the context of ordinary social obligations. What monasticism adds to ascetic theology is the establishment of a milieu in which ascetic practice can flourish and in which its fruits can be handed down in spiritual teaching through the writings of the monks. (ibid, pgs 53-55)

In summary, knowledge or gnosis is essential in all aspects mentioned above. Without understanding the circumstances and the current era, individuals cannot achieve genuine self-awareness or comprehend the nature of the Absolute. Engaging in ascetic practices without prudence or hunting demons without insight is dangerous and futile. In fact, the absence of discernment often leads people astray. Those who possess a clear understanding of their time can remain steadfast, while those who lack this awareness are easily influenced by the fluctuating opinions of others.