Asceticism has been discussed in several articles throughout this blog, but I am taking a much broader look at the subject in this series, incorporating aspects of both Eastern and Western thought. The concept of ascesis, derived from the Greek verb άσλέω meaning “train”, is basically one of discipline and training. The related term in the Indo-Aryan language Pāli is tapas (tapa or tapo) which expresses a similar notion but additionally contains imagery of heat and intensity to allude to an intense concentration that is almost like fire. In fact, the complexity of tapas is best seen through its application to ascetic activity. It denotes the hard work required, as well as the magical power and sacredness produced from it. This process allows for the practitioner to be taken beyond a merely human or profane realm. (Tapta Marga Asceticism and Initiation In Vedic India) Without the presence of tapas, spiritual development slows to a crawl. According to the literature, demonic activity can distract from contemplation and leave one feeling cold—icebound in thought. Therefore, in the spiritual psychology practiced in the Egyptian desert, thinking and demons are often considered one and the same.

For beginners, however, who are still in the purification stage and have not yet eradicated the very source of troubling thoughts and passions, the discipline of attention is based on a constant vigilance over their thoughts – a continual effort to “guard the thoughts” (κατασχεῖν τοὺς λογισμούς, cogitationes custodire) [in seminary, we used to refer to this as “keep custody of the eyes, boys!” Inclusion Mine.] and draw attention away from whatever may stand in the way of proper mindfulness. Chanting biblical texts can block-out out suggestions, all of which employ some sort of anchor to control the mind’s focus of attention. According to Diadochus of Photike, the mind should “contemplate this word alone at all times in its interior treasury so as not to return to the imagination.” Or, as Cassian explains, “A monk’s whole attention (omnis intentio) should constantly be fixed on one thing, and the beginnings and the roundabout turns of all his thoughts should be strenuously called back to this very thing – that is, to the recollection of God. (Inbar Graiver, Asceticism of the Mind, pgs. 90-91)

When we practice Unborn Mind Zen, we use the “Recollective Resolve”; listening and reflecting on texts such as The Dhammapada in Light of the Unborn helps to offset unhealthy mental habits. In a spiritual sense, asceticism involves willpower and transcendence over one’s desires, in order to reach higher spiritual levels. It means abstaining from immediate gratification for the sake of producing an exalted state of mindfulness. By adopting self-discipline and overcoming any form of overt skandhic self-identification, ascetics are able to reach more elevated spiritual realizations. All of this empowers one to overcome one of the most overt obstacles in the spiritual life—acedia:

Acedia: Laziness and carelessness were also the common signs of the demon of acedia (ἀκηδία). In early monastic literature this demonically inspired condition was often characterized by refusal to work, lack of desire to read or to pray, neglect of spiritual exercises, or laziness in the singing of psalms or in prayer. However, in his study of acedia Andrew Crislip draws attention to the lack of uniformity in early monastic descriptions of its symptoms: acedia afflicts not only the lazy and negligent but also those who are especially ascetic – “those who ‘try too hard’ in their asceticism, or who have channeled their ascetic drives into activities that, while normally approved, are enacted inappropriately.” In this case, the demon of acedia tempts the ascetic to undertake desirable and culturally sanctioned activities, but to perform them with the wrong motivation or in the wrong measure (e.g., too single-mindedly or too impatiently). In the latter case, the demon of acedia often impels the monk to reject the direction of his spiritual father. Refusal to submit to the guidance of a spiritual master put the ascetic in great risk. According to the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, some have “lost their wits” (εἰς ἔκστασιν φρενῶν ἐλθόντας) because they have “put their trust in their own works,” instead of consulting the elders. (ibid, pg. 107)

Along these lines, ancient monastic texts of spiritual advice that take the form of a conversation between a mentor and their student provide an insight into the conflict between the subjectivity of the trainee, battling against malevolent forces, and the teacher’s interpretation of those experiences. The “spiritual mentor”, or father figure, is imperative to this journey. This will also aid in accurately assessing what a healthy asceticism looks like versus an unhealthy form of it:

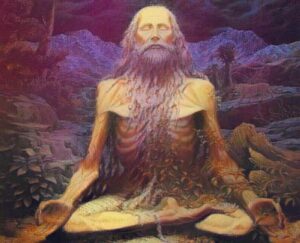

What basically distinguishes natural from unnatural asceticism is its attitude toward the body. Natural asceticism reduces material life to the utmost simplicity, restricting our physical needs to a minimum, but not maiming the body or otherwise deliberately causing it to suffer. Unnatural asceticism, on the other hand, seeks out special forms of mortification that torment the body and gratuitously inflict pain upon it. Thus it is a form of natural asceticism to wear cheap and plain clothing, whereas it is unnatural to wear fetters with iron spikes piercing the flesh. It is a form of natural asceticism to sleep on the ground, whereas it is unnatural to sleep on a bed of nails. It is a form of natural asceticism to live in a hut or a cave, instead of a well-appointed house, whereas it is unnatural to chain oneself to a rock or to stand permanently on top of a pillar. To refrain from marriage and sexual activity is natural asceticism; to castrate oneself is unnatural. (Vincent L. Wimbush & Richard Valantasis, Asceticism, pg. 9)

We must remember this as we keep exploring the concept of asceticism. People today usually associate it with strict rules, grueling restrictions, and sadness. Is that really true? We all know the arguments against asceticism well. Rather than rehearse them yet again, let’s try to find what can be said in its favor. We shall understand this best by looking at two basic components of the ascetic practice: withdrawal (anachoresis) and self-discipline (enkrateia).