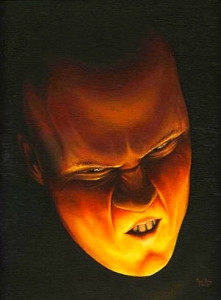

There is no greater enemy than one’s own thoughts run amok. The Dhammapada is layered with imagery that depicts this mental predicament, such as ‘what one thinks one becomes.’ Evola utilizes passages whose task is to arrest and erase these wanton beasts of the mind:

“As a fletcher straightens his arrow, so a wise man straightens his flickering and unstable thought, which is difficult to guard, difficult to hold.”

“As a fish taken from his world of water and thrown on dry land, so our thought flutters at the instant of escaping the dominion of Mara.”

“This intensive earnestness is the path that leads toward the deathless, in the same way that unreflective thought leads, instead, to death. He who possesses that earnestness does not die, while those who have unstable thought are as if already dead.”

A work of mine from 2002, The Dhammapada in Light of the Unborn, also conveys these savory teachings in like fashion:

Whosoever follow discursive thought-patterns is like one who daily mourns for phenomenal manifestations of the past and of the future; blind to the freedom of Mind centered in the Unborn, that Mind that transcends the bondage of time-bound reality, the mourner continues to grieve terrified of one’s own karma thus favoring the defiled twin of the bodhi-child—the alayavijnana, a “choice” that entraps the True Self-Essence into another round of spatial-spinning on the diurnal wheel of samsara.

But whoever follows faithfully the path of Unborn Freedom is joyful Now, thus transcending all dualistic notions of here or there; the rejoicing is bliss-filled since the defiled karma is cleansed revealing the shining splendor of the deathless face of the Unborn Essence.

Vigilance in the Recollective Resolve is the way of deathlessness.

Those who are careless walk in the nightmare realm of eternal dukkha and thus serve only death; but the vigilant despair not and thus shall never taste death.

Vigilance is the key factor that arrests and dismantles these destructive demons of the mind. Evola asserts that the Ariyan disciple needs to embrace this discipline of appamāda:

The discipline of constant control of the thought, with the elimination of its automatic forms, gradually achieves what in the texts is called appāmada, a term variously translated as “attention,” “earnestness,” “vigilance,” “diligence,” or “reflection.” It is, in point of fact, the opposite state to that of “letting oneself think,” it is the first form of entry into oneself, of an earnestness and of a fervid, austere concentration. When it is understood in this sense, as Max Muller has said,12- appamāda constitutes the base of every virtue-ye keel kusala dhammā sabbe te appamādamulakā. It is also said: “This intensive earnestness is the path that leads toward the deathless, in the same way that unreflective thought leads, instead, to death. He who possesses that earnestness does not die, while those who have unstable thought are as if already dead.” An ascetic “who delights in appamāda-in this austere concentration-and who guards against mental laxity, will advance like a fire, burning every bond, both great and small.” He “cannot err.” And when, thanks to this energy, all negligence is gone and he is calm, from his heights of wisdom he will look down on vain and agitated beings, as one who lives on a mountaintop looks down on those who live in the plains.’ (The Doctrine of Awakening, pg.110)

Once again he uses imagery from the Dhammapada; the Dhammapada in Light of the Unborn depicts this discipline as those who, instilled with the ‘Antecedent Recollective Resolve’, are forever perched on the ‘Olympian Mount of Primordial Perfection’ where the ever-vigilant Dragon-Eye surmounts these creeping forces of the undisciplined mind. St. Teresa of Avila uses similar imagery in her work, The Interior Castle, depicting all these creepy-crawly thoughts as lizards and other vermin who reside in the moat beneath the castle, and that are always attempting to scale the castle-walls, but are forestalled through that vigilant Recollective Resolve. The next step is then how to best reinforce these vigilant disciplines; Evola introduces ‘four instruments’ that will help to boost this determined effort.

The first instrument is substitution. When, in conceiving a particular idea, “there arise harmful and unworthy thoughts images of craving, of aversion, of blindness” (these are-let us remember-the three principal modes of manifestation of the āsava), then we must make this idea give place to another, beneficial idea. And in giving place to this beneficial idea it is possible that those deliberations and images will dissolve and that by this victory “the intimate spirit will be fortified, will become calm, united, and strong.” (ibid, pg.111)

This reminds me of a spiritual-director (back in my seminary years) who once taught a similar technique. Whenever negative thoughts emerge simply say “cancel-cancel” and then make a positive-thought substitution. It needs to be stressed that Evola demonstrates these instruments in place of trying to tackle these wily demons head-on, where the attempt will always prove futile—like trying to ‘sweep-away the wind.’ If one decides to utilize these techniques, then the Mind adept will come-out on top.

This leads us immediately to the second instrument: expulsion through horror or contempt. If, in the effort of passing from one image to another as the first method proscribes, unworthy thoughts, images of craving, aversion, or blindness still arise, then the unworthiness, the irrationality, and the misery they represent must be brought to mind. This is the simile: “Just as a woman or a man, young. flourishing and charming, round whose neck were tied the carcass of a snake, or the carcass of a dog, or a human carcass, would be filled with fear, horror, and loathing,” so, the perception of the unworthy character of those images or thoughts should produce an immediate and instinctive act of expulsion, from which their dispersion or neutralization would follow. Whenever an affective chord is touched, then by making an effort one must be able to feel contempt, shame, and disgust for the enjoyment or dislike that has arisen!’ (ibid, pg.111)

Ascetics of sundry traditions utilize this particular technique, like gazing on a dead corpse or spending time meditating in a cemetery on the transiency of life. Tibetan and Bonpo monks create meditational tools composed of skulls and bones, like the kapala or skull-cup, and the Khatvanga (described in detail in the Notes from the Iron Stupa series) or mystical-staff. These techniques and tools are very effective means of neutralizing destructive thoughts from gaining the upper-hand.

The third instrument is dissociation. When undesired images and thoughts arise, they must remain meaningless and be ignored. The simile is: as a man with good sight, who does not wish to observe what comes into his field of view at a particular moment can close his eyes or look elsewhere. When attention is resolutely withheld, the images or the tendencies are again restrained. (ibid, pg. 112-113)

Evola warns that this technique must not be misconstrued as ‘chasing thoughts away.’ This has the unintended effect of actually strengthening the thought-pattern, allowing the subconscious factors to gain control “according to the psychological law of converse effort.” Simply leave the thought alone by not giving it undue attention. Time and time again I used this device in the confessional when the penitent used to obsessively dwell on these subconscious factors that were ruling—and ruining—their lives.

The fourth instrument is gradual dismemberment. Make the thoughts vanish one after another successively…This method of making the infatuation disappear by separating its constituent parts one by one in a gradual series and considering them with a calm and objective eye one after another, provides, in the preparatory stage of the ascesis, an example of the very method of the whole process. And image corresponds to image. The state of one who achieves extinction is, in fact, likened to that of the man who runs parched and feverish under the scorching sun and who finally finds an alpine lake with fresh water in which he can bathe, and shade where he can relax and rest.” Another simile is given by the texts, still in connection with the method of dismemberment, it speaks of the pain that a man would feel in seeing a woman he favored flirt with others. He arrives, however, at this thought: “What if I were to abandon this favoring?”-inthe same spirit as he might say: “Why do I run? What if I were to walk calmly instead?” and then were to walk calmly. Having thus banished his inclination, that man can now witness the sight that pained him before with calm and indifference. (ibid, pg.113)

This technique of ‘dismemberment’ was a salient theme in the Notes from the Iron Stupa series, wherein the protagonist in the storyline underwent a series of shamanistic-initiations that *dismembered* quite effectively the skandhic-stranglehold.

Evola’s summation of the conflict with samsaric-imagery and its incessant thought quagmire is quite revealing:

It is not possible to avoid the appearance of images and inclinations in the mind: this occurs spontaneously and automatically until what is called voidness, sunna, is reached. To the disciple, to the fighting ascetic, some of these images are like strange and indifferent people whom we meet on the road and who pass by without attracting our attention. Others are like people we meet who wish to stop us: but since we see no point in it, we ourselves withdraw attention and pass on. Other images, however, are like people we meet and with whom we ourselves wish to walk, in the face of all reason. In this case we have to react and assert ourselves: the tendency of our will must be opposed from the start. (ibid, pg.114)

Once again we see the emphasis here on the will, not the individual will of the imagined persona, but rather the Tathatic-will of the Unborn. The latter is truly dominant if the Mind adept will allow IT to do ITs thing with effortless assurance—what we have referred to on many occasions within these blogs as the Wu-hsin effect. Evola, though, adds a fifth (to the other aforementioned four) variable that must also be present, and that is the ‘concentration of the heroic spirit’—this is that Recollective variable again—one that also takes on a transcendent, siddhi-like, quality:

The term iddhi (Skt.: siddhi) normally refers to powers of a supernormal character. Here it must be understood especially in relation to energies that are associated with warlike discipline-hatthisippādīni-without forgetting, however, that, on the path of awakening at least, we are dealing at the same time with forces on which the bodhi or panna element confers a quality that is not only human and that is not comparable to any that samsāra can offer, since it contains something of the “incomparable sureness” (anuttarassa yogakkhemassa). (emphasis mine) ibid, pg. 117

In conclusion of this section, what adepts in Tozen’s Zen School of the Unborn Mind refer to as, the Word, or Logos is something that Evola emphasizes here, too; it must be a determining factor in overcoming the lower impulses:

All this naturally demands the degree of mastery of the logos in us that enables our discriminating exactly between our thoughts. Those that can be organized and used in the required direction should be consolidated and established, working on the principle that the mind inclines toward what has been considered and pondered for a long time. In this respect, however, nothing can equal the benefits that come from a sense of innate dignity, as of a special race of spirit: then a reliable instinct will act and very little uncertainty will be felt in the task of “renouncing the low impulses of the mind.” (ibid, pg.115)